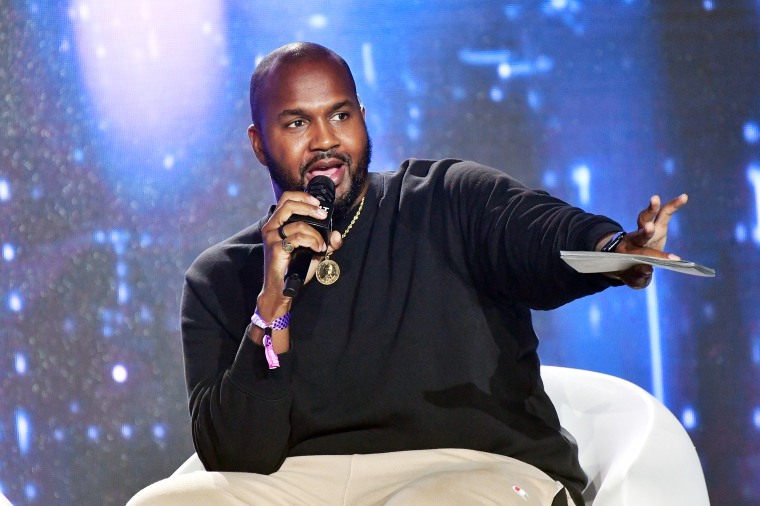

“It’s hard to tell an 18-year-old, who’s making millions of dollars, or hundreds of thousands of dollars a year, or a month, to do things differently,” said Lenny Santiago, Roc Nation’s senior vice president.

It’s a cycle on repeat: A beloved rapper is murdered. Family, friends and fans react online. The case is investigated yet typically goes unsolved. The hip-hop community calls for change, but there doesn’t seem to be an end in sight to the violence.

The recent shooting death of Migos rapper, Takeoff, on Nov. 1, has ignited a new conversation among artists and industry leaders. In order to disrupt this violent cycle and find possible solutions, they say, society must first stop blaming the hip-hop community, acknowledge that systemic issues have helped create the existing violence, and provide better options for Black inner-city youth to advance from broken systems.

“Hip-hop is culture,” said dead prez’s Stic, whose new book “The 5 Principles” touches on hip-hop’s journey toward well-being. “Hip-hop is BBoying breaking, emceeing, graffiti, knowledge of self, peace, love, joy, unity, having fun. That’s what hip-hop actually is. The violence we see in society is a product of the society. So I think hip-hop is the scapegoat for a lot of things.”

Since 2018, there have been at least two or more rappers per year killed as a result of gun violence. Studies looking at the life expectancy of rappers estimate that murder has been the cause of death of over 50% of dead rappers. They also show that their average age at the time of death was between 25 and 30 years old.

Some of those murders are now being explored in a new WE tv’s docuseries “Hip Hop Homicides,” which looks at the shooting deaths of rap artists including Pop Smoke, XXXTentacion and King Von. Van Lathan, one of the executive producers of the series, told NBC News that even though he feels rap has become “more violent,” it’s also important to note that “violence has become more accessible.”

“You can see more violent stuff,” he said. “If you want to do violence to someone, you know where they’re going to be at — more than ever before. And some of the music, if I’m being honest, reflects that increased accessibility to violence.”

Still, Lathan knows that even with more opportunities to exact violence, the root of these actions have always been systemic.

“It’s very hard to evolve out of dysfunction,” he explained. “If you grew up in a dysfunctional family, you’re going to develop some bad habits that carry over. The dysfunction and the sort of societal ills that we see are things that money doesn’t wash away. In some cases, money exacerbates some of these things.”

Although Lathan believes there should be more accountability in hip-hop from those who create the violence, rap artists can’t always be blamed for the violence that surrounds them or happens to them.

“When we talk about some of the things that are systemic, we’re talking about [King] Von had removed himself from his environment — he had removed himself from a lot of the dysfunction that he had grown up with,” he said of the 26-year-old rapper who was fatally shot outside an Atlanta night club in 2020. “But who he was and who he was made by, that was still a part of his life. So when he sees an op, an enemy, it’s ‘Let’s go have a fight.’ That fight ends up in him losing his life… The violence that they’ve had to lean on in order to preserve their life for a long time doesn’t just go away. People say, ‘Do better.’ It’s not that simple.”

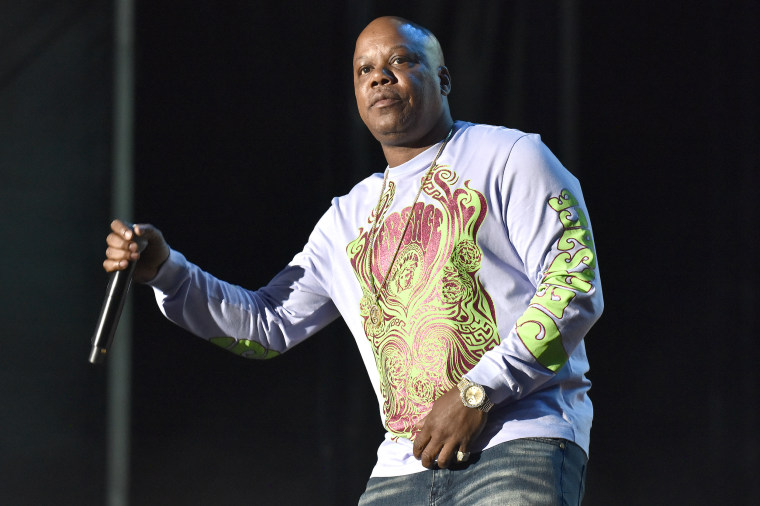

West Coast rapper Too $hort agreed, adding that a lot of the issues these young artists face are a result of a broken system that didn’t offer support.

“A lot of these kids lost their parents, their actual parents, to the war on drugs, the war on crime,” he said. “Their parents were taken away from the home, murdered, locked up, addicted, not there. And you have a lot of kids that raised themselves, they were raised by grandparents who couldn’t really do it the right way. Friends of the family, the brothers and sisters, uncles, aunties — like you have a broken community.”

‘Crack mothers, crack babies and AIDS patients’ — Mos Def, ‘Mathematics’

The crack epidemic of the ’80s and early ’90s devastated Black communities, who, due to racial segregation and discriminatory practices, often resided in inner cities or low-income neighborhoods. The use of crack in these communities contributed to a higher murder rate of young Black men, an elevated rate of incarcerations and a lower life expectancy.

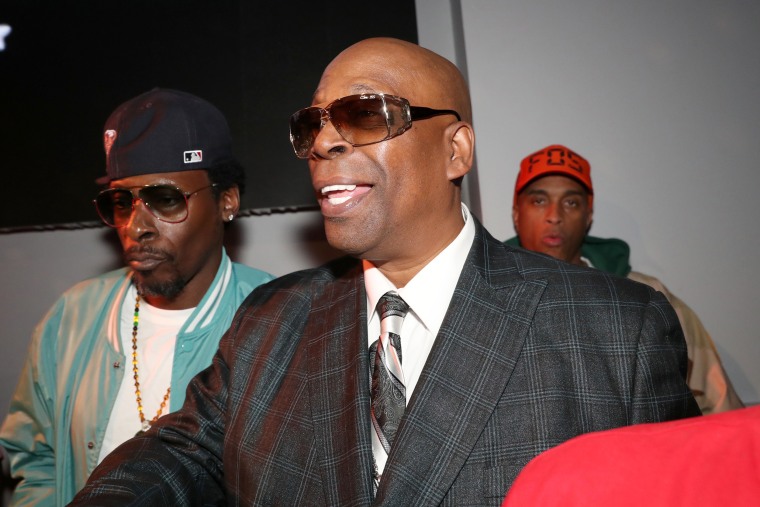

It was during this time, specifically the mid-80s, that the Golden Age of hip-hop emerged and produced artists like Grandmaster Caz of The Cold Crush Brothers. Caz said that in those days hip-hop music was used as a form of escape.

“This stems from our lack of resources,” he said. “Hip-hop was like, ‘OK, we don’t have this, we don’t have that. We’re broke, we can’t do this. We can’t go here. We can’t do that. So what are we gonna do? We took whatever was left, whatever we had at our disposal, and we created a culture around it.”

However, he said, the music quickly evolved from “escapism” to a focus on “getting paid” and getting “people out of the circumstances that they lived in.”

“The mindset of everybody changed to ‘Gotta be hard, gotta be mean, gotta be ready to kill or shoot somebody or defend this or do this,’” Caz explained. “And the narrative, not only from us, from the music, from the images, and of course, the movies, and all the other influences that go into our thought process. So now after the crack generation … that’s what they did. And that’s what’s permeating the landscape of hip-hop nowadays.”

He said the “crack generation” led to a major disconnect between the older generation and the younger one.

“The next generation had to fend for themselves — they didn’t get those lessons handed down from generation to generation that we did,” said Caz, who hosts a hip-hop bus tour around Harlem and the Bronx. “That generation was lost and gone and out in the streets.”

Lathan concurs, adding that society has become more of a “materialistic culture,” which only magnifies the systemic issues that plague it.

“It’s about the gram and about these chains and about these cars,” he said. “And we’re almost digital creations of our human selves. So, I don’t know if people think past, ‘I gotta have it. I gotta see it. It’s got to be mine.’ I think that has to do with a lot of the jealousy and envy of the people.”

‘I’m from Marcy Houses, where the boys die by the thousand’ — Jay Z, ‘Marcy Me’

For inner city young people with little to no resources, rap became a viable career option to make it out of their neighborhood. In fact, for many young men, like college basketball star turned Grammy-nominated rapper Dave East, there were only two real possibilities: make it to the NBA or become a rap star.

“That’s all my father would preach to us: Get good grades, play a sport, some s— like that,” he recalled. “They old school so they don’t know that rap — you could become a millionaire. My dad didn’t realize that until it happened to me.”

Too $hort added that for “a young kid, who may or may not be your future scholar or ballplayer,” rapping is the only real ticket out of their dire situation. “And a lot of them are taking advantage of it,” he said.

However, as Stic noted, just because they make it out of the hood it doesn’t mean they’ve left the hood mentality behind. “As human beings, there’s skillful and unskillful. We have to manage our mind, our emotions, our resources, no matter what culture that we’re in. And if we don’t, it’s going to show up in destructive ways,” he said.

‘If the truth is told, the youth can grow’ — Nas, ‘I Can’

As those destructive ways have become more visible these days thanks to social media, rap industry leaders like Roc Nation’s senior vice president, Lenny Santiago, are actively working to address the violence and counter it.

“That’s a responsibility all of us should have,” he said. “I definitely make it my business, my responsibility to school, to advise or to just help with friendly advice to anybody that I’m working with. Either from my experience, our experience, what we’ve seen, what we’ve been through before them — with everybody. And that’s always been the case.”

But, Lenny said, it’s not easy to break through to a young artist who may feel they don’t need advice when they’ve already achieved material success.

“It’s hard to tell an 18-year-old, who’s making millions of dollars, or hundreds of thousands of dollars a year, or a month, to do things differently,” he said. “When you have that money coming in, it’s almost like you always think it’s never gonna end. … You’re not trying to hear that advice that people are trying to give you. You’re not trying to hear, ‘You shouldn’t be going there’ or ‘You should be extra careful. He should have extra security, or you shouldn’t overspend on this … They’re looking at you like ‘Yeah, well, you’re just saying that because y’all don’t have it.’”

Dave East, 34, said he used to be just like those young artists who “didn’t want to hear that s— from nobody.”

“So you got to let them talk,” said East, who credits Nas, Syles P. and Snoop Dogg as some of his early mentors. “You got to peep their point of view, see how they feel about s—. And then from how they explain that to you, that’s when you give your advice. That’s when you say, ‘Look, I did that like that — that ain’t work. Maybe you should do this, like this. Or maybe you should fall back from that.’”

East admits, however, that with the release of his new album, “Book of David,” he’s chosen to move differently than a lot of the younger artists out there. East said he “works hard to filter out distractions and negative influences in his life.”

“We all got an expiration date at the end of the day and I’ve always lived life knowing that,” he said. “Whether it’s a violent death for just a random out-of-the-blue death. So I try to focus on my health … Mind my business. If it ain’t got nothing to do with me or my family … making me no money in a good, legal, positive way … I don’t even want to talk about it.”

Instead, East said, he’s focused on making music, acting and raising his two young daughters, Kobi and Kairi Chanel. “I go watch ‘Cocomelon’ and ‘Frozen’ and s— like that. That’s what makes me miss a lot of bulls—.”

‘There’s hope for the rest of us’ — XXXTentacion, ‘Hope’

Although some artists and industry leaders feel exhausted and frustrated by the current state of hip-hop and the ongoing violence, many believe there’s still plenty of hope.

“There’s hope because we’re an amazing, resilient, unbelievable people that has figured out almost every problem that America has saddled us with,” Lathan said.

Caz, who recently served as DJ and emcee to the Red Bull BC One World Finals for breakdancing in New York, agreed, saying “hip-hop as a culture is alive and well.”

“Hip-hop as a culture is like a roller coaster,” he explained. “It’s gonna go up. It’s gonna go down. It’s gonna go through tunnels. It’s gonna go around in circles. But guess what, it always lands on his wheels.”

Still, there is much work to be done when it comes to disrupting the violent cycle. Caz said while the culture will undoubtedly bounce back, “the music, the representation that comes out through rap music … needs amending.”

“Until that changes,” Caz added, “ we’re still going to keep getting these messages, unedited and unfiltered.”

Too $hort believes real changes can only happen when everyone takes responsibility for what’s going on in hip-hop.

“It’s not just the powers that be, it’s not the OGs, it’s not just the artists, it’s also the fans,” he said. “It’s all of us … The more you say, ‘I love this murder music,’ the more we gonna keep making it. The more the labels keep promoting this murder music and paying artists big money to do it more, the more we’re going to make it. Somebody’s got to break the chain.”

Chad is a professional journalist specializing in Hip-Hop culture and writing music reviews.